Explaining Anxiety to Kids

For me, talking to kids about anxiety can feel like a catch-22:

Talking about anxiety tends to make kids feel more anxious, which then makes it even harder to talk about!

For these children, I’ve noticed that it is particularly helpful to start the conversation early and build the child’s understanding of their diagnosis over time. In fact,

If anxiety is part of the referral question, I start the feedback process before I start the first test.

By introducing the concept of anxiety early, and in very small pieces, I’ve found children are better able to process what anxiety means for them without getting overwhelmed or shutting down.

As a result, kids have been leaving our feedback sessions feeling empowered by their newfound knowledge and ready to do the work to find out how anxiety can become their superpower.

Explaining “Helpful” Anxiety

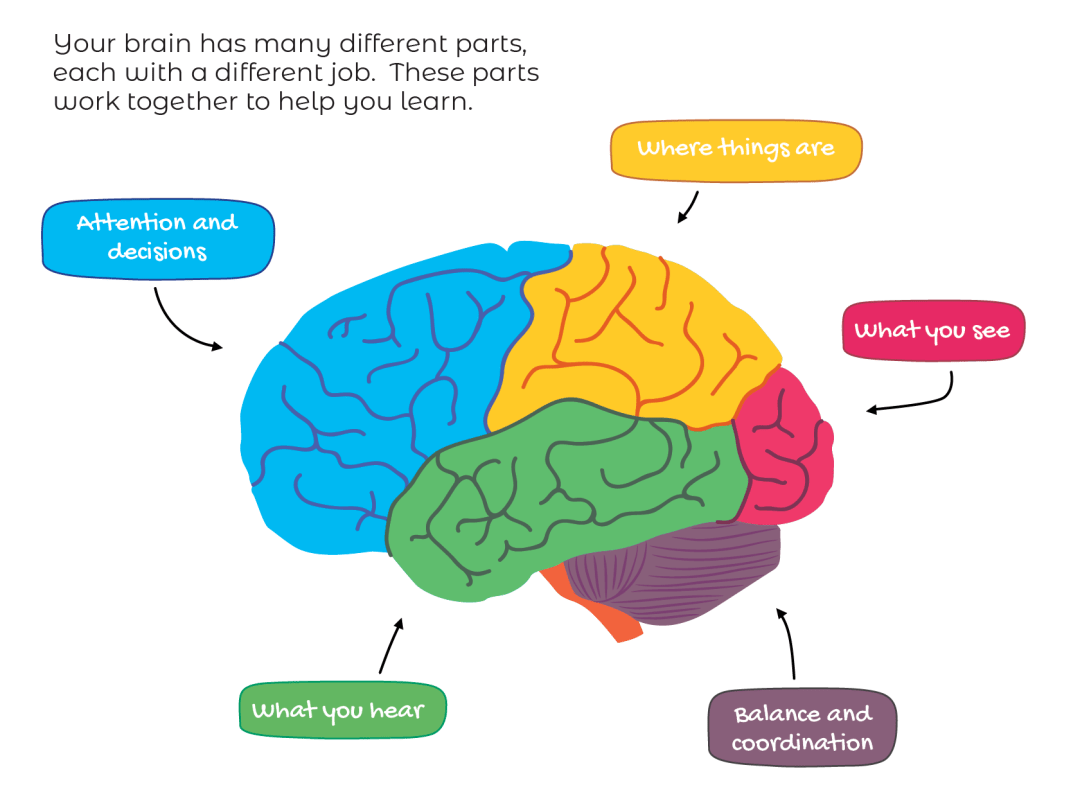

No matter what brings a child into my office, my first step is always the same: explore why we are there. I tell them that we will be doing different activities to help us understand how the different parts of their brain work together to help them learn and do different things.

Then, I explain the brain’s emotional system. This part of our brain is always “on,” and always scanning our environment to help keep us safe.

When anxiety is part of a child’s referral question, I make sure to spend time explaining that the brain has an “alarm” system that helps us know when something could be dangerous, using the handouts above.

For example, when we hear the sound of a charging tiger, our brain creates a feeling of anxiety and fear that prepares us to GET OUT OF THERE!

A very, very helpful feeling.

I let them know that a little bit of anxiety is helpful for everyday life, too. For example, being a little scared about a math test is our brain’s way of making sure we study for it.

The challenge is that sometimes our brain sounds the alarm when it shouldn’t, or the alarm may be really loud when it should just be a little warning.

In these cases, our frontal lobe can step in to help us figure out what to do.

I let children know that their frontal lobe is still growing, and may still be learning how to interpret the alarm, and what to do when it goes off.

Now we have paved the way to talk about what it means when the alarm is sounding off way too loudly and way too often.

In other words, when a child’s anxiety is unhelpful.

A Child-Friendly Definition of Anxiety

Once we’ve defined helpful and unhelpful anxiety, we can start to use these terms to help the child explain their experience.

As I learn more from the child over the course of the assessment, I start to document how they describe their strengths and challenges, so that we continue to build a shared vocabulary for how we talk about their brain.

Together we can create a definition of anxiety that the child will truly understand, because it uses their words and experiences.

To break it down, I’ve been using the following sentence frame:

When we break it down, there are 5 parts to this sentence frame:

- Identifying Strengths

- Naming Challenges

- Defining the Diagnosis

- You’re Not Alone!

- Let’s Make a Plan

Here’s what it looks like for anxiety.

Identifying the Strengths of Anxiety

Using the “brain-building” metaphor I reference most, explaining a diagnosis to a child begins with identifying their “highways” or strengths. In this situation, I may say something like:

“In our work together, we learned that your brain is built in a way that makes a lot of things come easily! These are like the super-fast highways in your brain.”

Here are some of the “highways” I’ve found when working with children who tend to have more anxious brains:

- Care a lot about others

- Observe before diving in

- First to respond when a friend is hurt or upset

- Think deeply about their decisions

- Attend to detail

- Want to do things well

- Have high standards for themselves

- Take their time on tasks to make sure they don’t make mistakes

- Curious

- Conscientious

- Highly motivated

- Ask a lot of questions

These strengths come from taking in a lot of information, noticing others, and caring about the world around us. They are not separate from the challenges of anxiety.

They are the benefits of anxiety.

Naming the Challenges of Anxiety

Of course, it is not fun to be anxious. The next piece of this puzzle is to name the challenges that arise and to validate the child’s experience.

Here’s what I typically say:

“In our work together, we also found some things that were tricky. These are your construction zones, or the skills your brain is working to build.”

While having an anxious brain brings a number of benefits, it also makes certain situations quite challenging. Children with anxiety may have difficulty:

- Paying attention

- Adjusting to changes in the schedule or agenda

- Knowing how to react or interpret what someone says on the playground

- Shifting their brain away from unwanted thoughts

- Breaking tasks into small parts

- Showing what they know on tests or when they’re called on in class

- Saying what they mean

- Doing something new or challenging

- Controlling their reaction when they feel pressured or threatened

As is often the case, we can draw a connection between a child’s highways and construction zones.

For example, people with anxious brains tend to be very empathetic and attentive friends, but may also sometimes care so much about what others think that it can be distracting or paralyzing.

Defining Anxiety for the Child

A diagnosis is a way of bringing the highways and construction zones together. This may sound like:

“It turns out, many people have highways and construction zones just like yours. This pattern happens a lot, and we call it anxiety. Some anxiety is really helpful, but too much anxiety is not very helpful and can really get in the way.”

To further define anxiety for the child, I’ve found it most helpful to use the child’s experience and their words. This makes it easier for the child to understand what we mean.

Here are a few examples of the ways I’ve defined anxiety for the children I’ve worked with. “For you, anxiety means…

- “Your brain is built in a way that makes you very attentive to others’ needs, and a great friend! It also may mean that sometimes you may focus more on other people’s opinions than your own.”

- “Your brain is taking in a lot of information from the world around you all the time. That’s part of why you can come up with so many creative ideas! At times you may also feel overwhelmed by all that information and not know what to do.”

- “You care a lot about what you do and doing well is very important to you. Sometimes, your brain’s desire to get things ‘right’ can get in the way of getting them done.”

- “Your brain likes knowing what will happen and having a plan. Sometimes your brain has a hard time because things didn’t go as planned. This is when you ‘flip your lid.’”

You’re Not Alone!

During a feedback session, I find it helpful to show kids a short video or examples of other individuals who have made anxiety their superpower. Here are a few resources:

- The Hand Model of the Brain: A short explanation of what happens when our brain sounds a false alarm and what we can do to help.

- A Guide to Anxiety for Kids: A short video normalizing anxiety.

- All Birds Have Anxiety: A cute picture book explaining the many ways anxiety can show up.

- Inside Out (Pixar): I highly recommend the movie as a conversation starter for the importance of all our big feelings!

- How to Fight Procrastination Anxiety: Help for ADHD brains experiencing anxiety

- Wikipedia’s List of People with Anxiety: A long list of athletes, artists, scientists, and more, such as Justin Bieber and Sarah Silverman.

- Celebrities with Anxiety: A slideshow of well-known folks from Oprah to Adele.

Let’s Make a Plan!

Finally, the child and I come up with a list of tools and strategies that will be helpful for maximizing their strengths and building new skills. For example:

- “You will be working with a therapist to learn some ways to help your brain make a plan when you’re feeling really overwhelmed.”

- “Mindfulness will help you learn different ways to notice your thoughts instead of getting stuck in them.”

- “You’ll be getting extra time on tests so you don’t feel as rushed.”

- “Your teacher is going to start checking in with you at the beginning of the day to go over any changes in the schedule or things that may be surprising.”

- “The counselor is a great resource for helping you stay on top of assignments and ask for help from teachers when you need it.”

- “When things are hard in the moment, you can use the 5-4-3-2-1 strategy to ground yourself and figure out what to do next.”

- “We’re starting a peer counseling group and I think you’d be a great addition as someone who really knows how to help others!”

In this way, the child becomes a more active participant in their intervention because they know exactly why it’s happening. This is especially important for anxious children who benefit from knowing the “why.”

Helping Parents Help their Child

Whenever I have these conversations with children, I always involve the parents. This language is hugely helpful for them as well.

So many parents have reported that attending their child’s feedback session is when it all “clicked.”

Furthermore, in these sessions, I have a chance to model for the parents what it might sound like to talk to their child about their diagnosis in an affirming, empowering, and positive way.

Once we have the language for talking to their child, I help parents share it with the school and other adults using this summary sheet, so that there is a common vocabulary among the child’s entire support team.

A Tool for Talking About Anxiety

If the framework above is helpful to you, The Brain Building Book may be a valuable addition when working with elementary-age children.

I’ve found that the visuals in this book are particularly helpful for kids who struggle with anxiety, and make it much easier for them to talk about their experiences.

Throughout the testing sessions, we document our conversation in the book and review it at the feedback session. This way when we get to their diagnosis, they are already familiar with all the pieces.

In fact, kids leave feeling empowered by their discoveries. As one child told me at the end of our feedback session:

“Anxiety is a pain to have at first, but once you learn how to use it, it’s really helpful. With great power comes great responsibility!” – Alex, 5th grade

You're not alone in your child's health and wellness journey. Together, we can create a path of renewal and hope.

Client Portal

Join Our Team

Blog

Providers

Services

About

ballard clinic

We are experts in helping children, adolescents,

young adults, and families.

Contact

Contact

Contact

Contact

Appointment

privacy policy

all rights reserved

WAYZATA ADDRESS: 1907 Wayzata Boulevard E., Suite 100, Wayzata, MN 55391

612-787-2344

EDINA ADDRESS: 7301 Ohms Lane, Suite 195, Edina, MN 55439

612-787-2344